The death on September 16 of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian Kurdish woman, in the custody of Iran’s so-called morality police for allegedly violating the country’s ultra-conservative dress code, sparked massive anti-government demonstrations.

The protests were initially started by women tired of obeying the harsh rules of the Islamic regime, where they have almost no rights, not even the right to go bare-headed or to sing alone on stage.

Later, many men joined the street demonstrations. Despite the violent interventions of the authorities – 243 deaths, 23 children among, thousands of arrests, and a weak political support from abroad, the protests not only did not stop, but 40 days after the young woman’s death, they intensified.

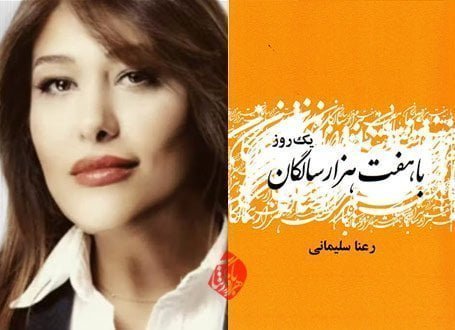

PRESShub spoke to Iranian writer Rana Soleimani about the harsh living conditions for women in Iran, one of the toughest patriarchal societies and the chances of the Islamic regime falling.

Her first book, Lorca on the Street of Angels, was banned from publication by the Iranian authorities. Although in Iran she participated in many literary contests, she was not among the winners because of her refusal to conform to the rules of the Islamic Republic.

Finally, Rana Soleimani left Iran, and since 2014 she has been living in Sweden. Rana’s books include The Ulysses Syndrome, a novel published in London that describes the story of a Jewish woman forced to leave Iran with her child, and Viva la Vida, the story of four women in Ervin Prison, each accused of a different crime. This book was an Iranian bestseller abroad last year.

The most important statements of Rana Soleimani

The Ministry of Culture and Order of the Islamic Republic of Iran is responsible for limiting access to any non-Islamic content and preventing the promotion of foreign culture in the Islamic Republic.

The big problem of Iranian society is that censorship does not only operate in the field of fiction, but also manifests itself on academic, scientific, theatrical, cinematographic productions, etc.

Solo performance by women on stage, in a play or in a film, is prohibited, and touching a woman’s body or hair is prohibited altogether.

Iran’s Islamic Penal Code is the reflection of a patriarchal society among the harshest, where women’s rights are half of men’s rights.

There have also been protest movements in recent years generated by the obligation to wear the hijab. The protest movement of the Elkhebal Street girls since January 2016 turned the issue of compulsory hijab into one of the main issues at the political and social level.

The problem is that, as the regime itself admits, culture has been a fortress that they have not been able to conquer so far, remaining one of the main pillars of people’s resistance against the regime.

It can now be said that the dictatorial regime has lost the game and that the spirit of the collectivity has changed. The Islamic Republic must be removed. The main problem is not the removal of the veil. People want civil rights and they want those rights respected.

PRESShub: You left Iran and arrived in Sweden in 2014. Why did you leave your home country and how many times have you returned to Iran?

I migrated for the sake of the word. When I left, my suitcase was empty, but my soul was full of words that I did not dare to say in my country. I am a writer and the goal of every writer is to put into words what is happening around her. Having in mind the restrictions in my own country, I had no choice but to live in exile. It is an auto imposed exile which remains like a prison at its very core. Unfortunately, no, I could not go back to Iran.

Although you studied Business Economics at Tehran University, later on you became a writer, member of the Iranian Literature Centre and the author of 5 books in Farsi. How did the transition from Economics to Literature take place?

I had dreamed of becoming a writer since childhood. In adolescence I had a great interest in French literature and a special attraction for Marcel Proust’ novel In Search of Lost Time. Initially, when I had to attend a university, I opted for French Literature, but having in mind that I did not have any certain future ahead by studying Literature and due to my fathers’ insistence, I started studying Economics.

However, back then one could not have any certainty about the future with a career path in Economics either. That was because after the Islamic Revolution in Iran, the Supreme Leader Khomeini declared that the country did not need any economists and that the Economics was good for donkeys.

I should say that I wrote my final thesis on the theme of the fight against poverty in the Iranian society.

Of course, my thesis received no critical evaluation or appreciation of any sort. Later on, after my studies in Economics, I initiated getting familiar with courses on Literature and Philosophy.

Your first book, Lorca on Fereshteh Street, was banned from publishing by the Ministry of Guidance in Iran. What does the Ministry of Order really mean? Why did the authorities ban your book and how difficult was it for you to overcome censorship in Iran?

The Ministry of Culture and Guidance of the Islamic Republic of Iran is responsible for limiting the access to any non-Islamic content and for preventing the promotion of any foreign culture in the Islamic Republic.

My first book, Lorca on the Fereshteh Street was initially banned from publication because of the problems it encountered with the official censorship. Two years later this book was published after the elimination of words and concepts from its content.

In Iran, a book is automatically officially reviewed as long as it contains a slightest reference to an emotional relationship between two persons, a critique towards a public figure, or a social critique that could smoothly lead into politics.

The biggest problem of the Iranian Society is that the official censorship does not operate only in the literary field, but it is present everywhere, in the academic and the scientific fields, in the theatrical and cinema production etc.

One of the most important aspects to stress out in this regard is that the censorship pressure and the feeling of suffocation are very big among the people. This is also as a result of the fact that the authorities use to send to prison and even kill popular writers and journalists, under various pretexts. This shows that the Islamic Republic is afraid of spreading awareness among the people.

Nowadays, it should be noted that many women from the poetic and fictional spheres try to express their spiritual greatness and their social status with a critical outlook, pleading for an ideal state in front of their audience. They try to show a reaction in this way, to refrain from being passive in the face of the social realities that regard them directly. This type of attitude will continue to be subjected to increasing censorship and social pressure.

Are there any restrictions that are applied only to female writers exclusively and not to male writers as well? I know, for example, that female singers are not allowed to perform individually on stage.

In general, the goal of the officials of the Islamic Republic is to suppress women. Therefore, they oppose any activity that is not in line with this goal.

As you singled out very well, women are forbidden from performing solo on stage, in a theatre play or in a movie. Touching a woman’s body or hair is forbidden at all.

These sorts of restrictions in the Iranian patriarchal society provoke women’s discontent and protest, protest which they tend to express in art, in painting, in music, in literature.

The women transform their negative furry into a positive artistic product through the means of the artistic creation. The majority of the Iranian female writers write about women’s problems, criticising the patriarchal culture, their husbands’ infidelity, the loss of child custody, the gender inequality and so on.

On the other hand, as long as men are not subjected to similar restrictions and as long as they have the possibility of benefiting from various experiences such as taking part in wars or getting involved socially and politically, they tend to embrace more diverse themes in their literary writings.

You have been living in Sweden for over 8 years. How different do you find the status of women in Sweden by comparison to the status of women in Iran and how well do you manage to adapt yourself to the Iranian society?

I am an Iranian woman myself, a person who was considered a citizen of a second rank in her country because of her gender. It is hard to fully understand what it means to be a woman in an unequal and insecure society unless you are and live in that particular society.

I have been living in Sweden, one of the promoter states of equal rights for women and men. However, the fact that I am here has its own cost, but this cost is low when having in mind the benefits.

In the first years when I arrived in Sweden I met an Iranian woman who told me that we, the Iranian women, are like a tree under the rain. It is enough for us to be hit by a storm and we will be wet by our own tears.

It is a beautiful simile this of a person with a tree because a tree is a product of the soil in which it grows, it is the result of the environment and society in which it developed. Well, we are trees, but we are also separated from our roots.

Iran’s Islamic Penal Code continues to provide for corporal judicial punishments amounting to torture, including amputation, flogging, blinding, crucifixion and stoning. What is the impact of the Islamic Penal Code on society? How much does it affect the ordinary life of the Iranian people? I think you documented this aspect in your books.

I documented some aspects of the Islamic Penal Code regarding women. The Islamic Penal Code is the reflection of one of the toughest patriarchal societies, in which women’s rights represent half of men’s rights. For example, for adultery a women receives the capital punishment. According to this penal code, there is a right to a dowry, but a woman’s right to a dowry means half of the dowry that a man is entitled to.

Viva la Vida is one the books in which I exposed aspects of the islamic Penal Code regarding women. The book is the story of four women incarcerated in the Ervin prison, each of them being accused of a different crime. The theme of this book is bitter and dark, as it is about women and executions in Iran. In order to write this book I read

scattered memoirs and I met some of these women. The emotional impact left by these women’s testimonies was so strong that I was left with such a feeling as if I personally lived their experiences. And I have always told myself that I was a strong woman if I could survive those testimonies. After I wrote that book I had a severe depression. Still, I consider that I have the obligation to continue writing in order to expose the Iranian people’s suffering, the Iranian women’s suffering as it should be recorded by history.

The attention of the entire world is focused on Iran nowadays as a result of the ongoing women’s protests that started over a month ago, with Mahsa Amini’s death in the Morality Police custody where she was taken for not wearing the hijab correctly. Although the protests spurred locally, at Mahsa Amini’s funeral in a Kurdish town, they soon spread throughout the entire country. Why do you think these protests spread so fast, to mobilise not only women, but also men?

Yes, Mahsa Amini’s unfair death attracted after it the Iranian women and men’s protests despite any belonging to ideology, religion, ethnicity or tribe. Gina Mahsa’s death was an event which left a profound emptiness in people’s hearts, breaking the rigid structure of reality, transforming the street into a place of openness towards something new, towards humanity and freedom.

Wearing hijab became obligatory for all Iranian women in 1983. The criminal punishment for those violating the law was introduced in the 1990s and ranged from imprisonment to fines. It means that women have been subjected to this law for almost 40 years. Why did we not see similar protests (in terms of magnitude) against wearing hijab before?

According to the Iranian Islamic Penal Code, the women who appear today in public without wearing the Sharia veil can receive a punishment oscillating from 10 days to 2 months of prison or they can get a fine.

There were protest movements in the past generated by the compulsory wearing of hijab. The girls’ protest movement in Elkhebal Street, in January 2016, transformed the theme of compulsory hijab into one of the main themes at the social and the political levels.

Back then the women hung their veils on sticks, climbed platforms and protested in this way. Many of those women who became known as the Girls of the Street Revolution, were arrested, and some of them were sentenced in courts to prison and flogging.

Now the women burn their veils and they want to remove the Islamic Republic from power. They are powerful women, pioneer women, and the men support them so that together they can win the fight against evil.

What is peculiar to the current protests in Iran is not only the police brutality against all the protestors, but also the fact that some of the targets of this raw brutality are children, high school students of 15, 16 years old. Several female adolescents have been reported dead in the media, after being beaten with batons. How do you comment on this police barbarity unseen in protests elsewhere in the world, at least not in this form?

Yes. What the government has done in the streets and in schools is not a suppression of the right to freedom but the trampling on the right to life of children. And this is a criminal act. This government kills its children, while the schools and the universities become a slaughterhouse.

The authorities kill the best children of the country and hide their bodies from their families.

What can be said about the fact that the children leave the house and never come back?

So far 243 people have been killed in the streets during the protests.

The Committee on the Rights of the Child asked the Islamic Republic to adhere to its international human rights obligations, especially its obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Children’s right to have their voice heard, including girls’ right, should not be suppressed by any form of violence or force.

In a speech delivered at the beginning of this month, the Iran Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei declared that “ the protests were engineered by America and the occupying, false Zionist regime, as well as their paid agents, with the help of some traitorous Iranians abroad”. What do you think about this declaration?

These declarations have been made by Khamenei and by other regime leaders for years, each time the regime found itself in a threatening situation. They are not new.

This is the classic rhetoric of the last 45 years against any opposing voice of the regime.

The statements led to the regime to be mocked and ridiculed by people. Even more, many officials of the regime do not take them seriously. The problem is that if the authorities want to legitimise themselves in front of the protestors, there is nothing in this system to defend. Therefore, the easiest way for the regime is to resort to these foreign conspiracies in their explanations.

In the same speech, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei said there were two types of people protesting on the street, those who are „agents of the enemy… or aligned with the enemy” and those who got carried away. While for the first group he recommended the authorities to carry out their security and judicial duties, he added that “cultural programs” should be implemented with regard to the second group. What do you think Khamenei meant by those “cultural programs” ?

These cultural programs started after the Revolution in 1975, once with the attack on all cultural institutions and they continued with the cultural revolution in universities and educational institutions. There has not been a single day of pause from their implementation since then.

The problem is that, as the government itself recognises it, culture has been a fortress which it did not manage to conquer, representing one of the main pillars of people’s resistance against the regime. Once with the arrival to power of the presidential government, the pressure on the side of the Ministry of Guidance doubled and a new censorship attack took place which led to the suppression of all cultural activists. What the authorities have in mind by the so-called “cultural programs” is represented by the same policy of repression that has been seen by now.

There have been pro government street demonstrations, in which many women took part, simultaneously with the current street protests against the government. How can these pro government protests be explained ?

Also in the past there have been demonstrations in favour of the government, but all those demonstrations were organised by governmental institutions. This type of gathering is not unprecedented and the government has been using various tactics to attract people to them, ranging from pressure exerted on the government employees to take part in these meetings, to the distribution of food, drinks and goods for the lower classes. In recent years, on various occasions, especially in the context of street protests against the government, the authorities tried to prove their legitimacy by organising such gatherings.

What has always been interesting to remark, was the small number of participants. And this number keeps on getting lower and lower with every pro-government demonstration. In the last weeks, this number was so small that the authorities had to use faked photos by the media, showing crowds of supporters, several times bigger than the real ones. In some cases the authorities were forced to cancel such gatherings because of the lack of support from their adherents.

A common demand among the Iranian protests is “death to the dictator”. Do you think these protests could lead to an end of the Islamic Republic, as it happened in some countries during the Arab Spring? Or rather, do you think there is a chance for the current Islamic regime to come to peace with the protestors by accepting some of their demands, such as the elimination of the obligatory hijab in public?

It can be said that the dictatorial regime has lost the game and that the collective spirit has changed. The Islamic Republic must be removed. This republic issues fatwas against the people. Its representatives are like the sun worshipers who easily change colour. A door opened by them for the people will mean another thousand doors shut in the way of modernisation.

The main problem is not the removal of headscarves. The people want civil rights and they want these civil rights to be respected.

Also, we, the people, ask for the rights of minorities, ethnical and gender minorities to be respected. We want gender equality. Furthermore, Iran is a rich country in natural reserves. To be able to live in prosperity it is necessary to remove from power those who keep on looting it.

Even the mullahs should be obliged to go on streets in regular clothes or at least to respectfully pass by the women and the girls when they wear thin clothes. In Iran, the language and world are black and white, but we want a modern and colourful world.

Although important public figures and individual politicians all over the world have shown their solidarity with the Iranian people, some of them with symbolic gestures such as cutting their hair in public, yesterday a group 77 of Iranians in exile, human rights activists and families of political prisoners signed an open letter asking for “the free world” to do more against the regime. How do you think the West, especially the USA, could do more? What concrete measures should they take in this context, apart from the sanctions that were already imposed on particular officials?

The aim of these protests is the removal of the islamic regime and the formation of a new democratic one. To achieve this aim, the Iranian people can not count on the support of the USA or the European Union because the Iranians have already seen what the foreign help meant when it came to other states in the region.

The United States and the members of the European Union have their own policies through which they follow their own interests, as they have been making concessions to the regime of the Islamic Republic for years. None of these states were sympathetic to the Iranians. The fall of the Islamic Republic is certain, maybe not immediately, but it will definitely happen.

The days of the Islamic Republic regime have been numbered since 1396 and they are getting closer to their end with every uprising

Do you think someday you will be able to return to Iran?

Even though I live in exile, I have a bigger dream besides returning to Iran. This dream means peace and tranquility for the people of my land.

„The world does not stay like this, it keeps putting everyone’s wheels in their place – Saib Tabrizi.

The interview with Rana Soleimani was conducted by e-mail, in English.

Follow PressHUB on Google News !

[…] This article was published on 30 October 2022 at Press Hub. […]

[…] Тази статия бе публикувана на 30 октомври 2022 г. на румънския сайт Press Hub. […]