It’s May 1952. Julius Márton, a bricklayer and carpenter, tears a piece of paper from a cement bag and with a carpenter’s pencil writes a note which he hides in a matchbox in the wall of the Casino he is working on. He’s a political prisoner, sentenced first to nine and then three years of hard prison, for fraudulent border crossing.

He doesn’t know when he will go out and be able to return home, to Cisnădie, nor if he will escape with his life. His note, nestled in the walls, will remain a sign that he has passed through. That in the spring when he turns 50, he is still alive.

Seventy years later, the Casino’s renovations are uncovering Julius’ note. The mayor of Constanta makes public the message that touched everyone. Writing to an unknown reader, he writes to us with impressive warmth and dignity.

Citește și: A true information used in a fake news. When peope who wear masks are fined

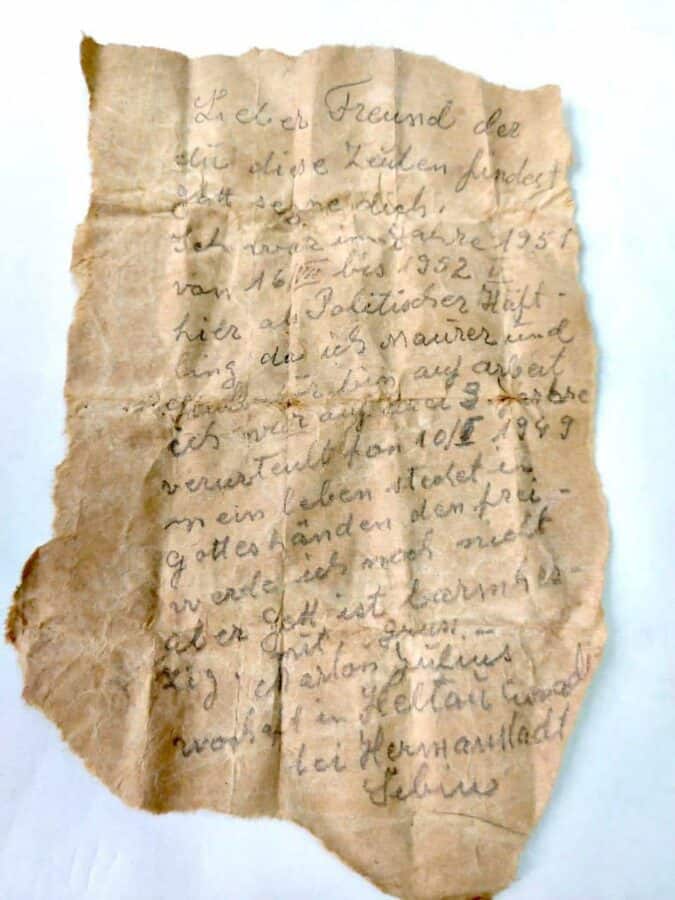

„Beloved friend who will find these lines, God bless you”

I have been here as a political prisoner since 1951, 16 VII, until [now – ed.] 1952, V (May – ed.), being a bricklayer and carpenter at work.

I was sentenced to 3 years and since the 10th I (January – ed.) 1949 my life is in God’s hands, for I will not be free soon. But God is merciful.

Yours faithfully, Marton Julius, resident at Heltau-Cisnădie, near Hermannstadt-Sibiu.„

This is the content of the note left in the wall of the Casino in Constanta.

It took a lot of courage to write these lines, to hide them in the matchbox, in the walls, inmates being under constant surveillance on the site.

But he had the lucidity and hope it takes for such a gesture.

He had faith in those who would find him that they would be from a better world, blessed friends.

Who is the man who did this? Why did an „apolitical” builder end up politically condemned to forced labor far from home?

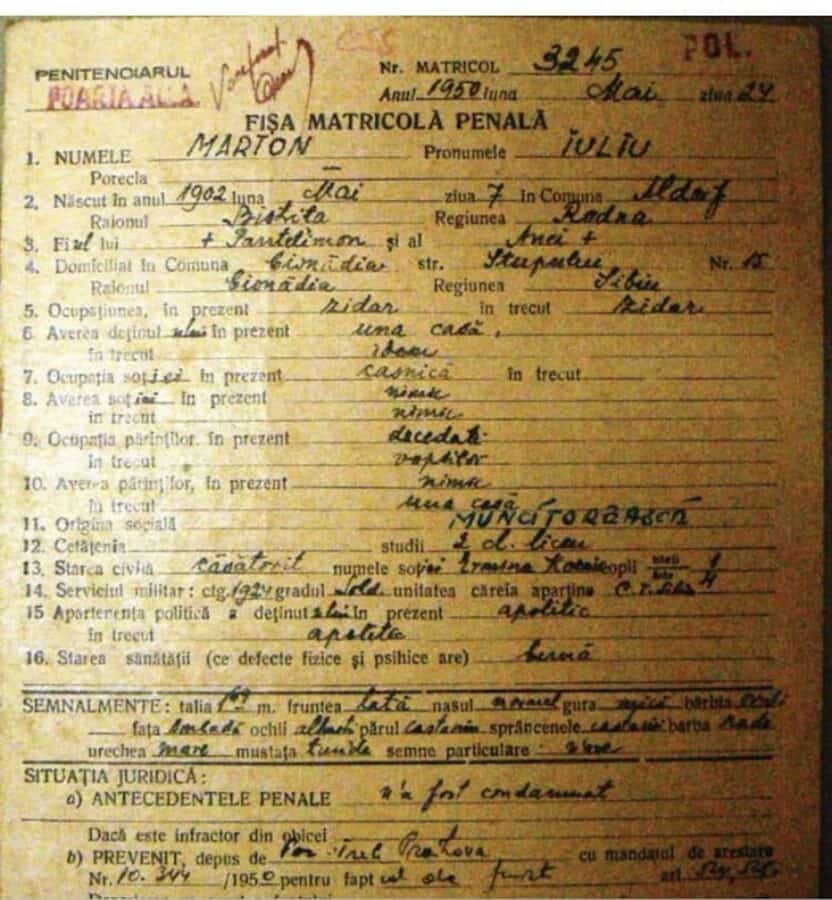

„Iulius Marton had completed two classes of high school and had satisfied his military service. He was ‘apolitical’ and yet he was in the camp, after having been sent directly from the Security Police and the Sibiu Tribunal to Poarta Albă and not to an execution penitentiary: he had been sentenced to a correctional punishment and, above all, he had a mason’s qualification, and his work capacity should not be wasted in a cell, but put to the service of the regime, as its servant.

The Saxon bricklayer from Cisnădie was arrested, as he says, on 10 January 1949, but in the Securitate records it appears that his deprivation of liberty began on 24 February”, writes Marius Oprea, historian and former president of the Institute for the Investigation of the Crimes of Communism and the Memory of Romanian Exile (IICCMER).

Julius Márton was born on May 7, 1902, in Unirea (in German- Wallendorf, in Hungarian- Aldorf, Bistrita-Năsăud), he was married to Hermine from Heltau, father of six children, one of them dead at the age of one year.

Read also: 3 of the biggest lies about insects based food in European Union

He was punished because he wanted to be with his family

The reason for his imprisoment, according to the historian Marius Oprea, who has consulted the criminal record of the convict, is fraudulent border crossing.

„He had finally returned home – how, only he and perhaps his children know – from Germany (he was past 40 and unlikely to have been drafted into German units). Perhaps, being a qualified bricklayer, he had been concentrated at work in the Reich during the war, like many of his compatriots in Romania, and at the end of it had ended up as a prisoner.

Not having gone through the formalities of repatriation, but simply entering the country, consumed by longing for his children and wife, he was considered, in the paranoia of the Securitate, first of all a possible spy and received that large sentence of nine years, a classification that was later replaced because of the inconsistency of the evidence.

This is not a unique case. There are thousands of prisoners, Saxons and Swabians from Transylvania and Banat, who either went to work or joined the German army, passed through the long odyssey of returning home from the Allied ‘sorting stations in the West, ending up in the same way – either convicted of ‘fraudulent crossing’ the border on their return home, or sent directly to forced labour in the USSR”, explains Marius Oprea.

I set to Cisnădie in the hope that I could learn more about who Julius Márton was. From the criminal record sheet, published by IICCMER, we already knew that he lived on Stupului Street, at number 15.

Stupului Street looks now just like our world: a chaos of new architecture, with wealthy houses and, from place to place, an old one, partially ruined, inhabited by the old people or abandoned.

Maria lives at one of the first houses on the street and when I ask about the Márton family, she is eager to help. Yes, she remembers them. But they weren’t staying where number 15 is now – the numbering has changed – but in the house upstream, the one with the liliac at the gate.

They had a blonde girl, very pretty, a nurse. But the most things knows about them Olga, Marton’s neighbour.

I find Olga Borzan in the courtyard, in the sun. She was born there, in the house on Stupului Street, in 1949. And she remembers the family very well, even though she was a child. Especially since Iulius, the neighbouring bricklayer, built her the little room where she lives now.

After that they built the big house, with a storey, from the road. But the small room, where Olga sits now on the bench in the sun, was built by Iulius Márton in the 1960s (Olga thinks in ’66) from the bricks of the stable.

„When the Collective was made, they took the cow away from us and then my folks said, let’s make a room out of the barn, there’s nothing else we can do with it. We were 13 brothers and sisters and any small room would be useful. Now I live in it. Our neighbour Julius was very industrious and helpful, he made us this room for no money.

That’s what he did, he helped everyone without money. Wherever he was called he went and worked, but he didn’t get paid. That’s how the Saxons were, very hardworking and helpful.

He taught us, when we were kids, to play, to fight with snowballs. He would come and show us how to make lumps and how to hit them. I was a child, but I remember him well. He was tall, had wide eyes and wasn’t fat.

With the Márton girls we were friends, we told stories, we played.”

She knows nothing of any deportation or conviction of Julius, the neighbor. „They didn’t tell us kids, maybe my parents knew, but they kept us from these things.”

One of his kids were killed

Olga hesitates, but still says that „people will cluck anyway”, that Julius and Hermine had a daughter, Irene, „a bit sickly”.

„She didn’t hurt anyone, she was like a big baby. All day long she would walk around and crochet. She crocheted tablecloths, curtains, everything.

She walked at night, and crocheted by the moonlight. Hermine sold some of her laces to the girls at the factory. But Irene ended badly. She was killed by some bastards.”

What Julius Márton really looked like, we can deduce from his criminal record: „He was un meter and sixty nine tall, broad forehead, normal nose, small mouth, oval chin, brown hair and blue eyes”.

And his only „fortune” was the small house on Stupului Street, with a liliac at the gate. And the two hands with which he worked „without pay” for anyone who called him for help. He went to high school for two years.

„From the year he was born, we deduce that he went to school before the Unification and then only learned German and Hungarian, which explains why he wrote the note in German. Correct German and that is to be appreciated for a bricklayer.

He probably learned Romanian as an adult, but he didn’t know how to write Romanian,” says Gerhild Rudolf of the Teutsch House in Sibiu.

Church files were kept till this days

The town hall does not have any data on the Márton family, I am told that the town archives were burned during the Revolution. At the Evangelical Church, however, we find the family record kept in the church records.

The priest László-Zoran Kézdi from Cisnădie reads us the page on which births, deaths, marriages and some events in the life of the Márton family are listed.

Although he was not born in Cisnădie, but in Wallendorf, in Bistrița, because the parishioners of Cisnădie were given a church card when they settled in the town, the Márton family was also received one.

So, Julius Márton was born on 7 May 1902 in Wallendorf-Bistrița and died on 3 October 1971. He married at the age of 25 with Hermine König, who was born in 1908 and died in 1989.

They had six children: Hermine, Iulius, Hilda, Irene, Gerhart and Erica. Gerhart died a year after his birth. His children emigrated to Germany, the last daughter died in 2021.

When he was arrested, he had five children at home.

„Although our registers record events in the family, Julius Márton’s only record is the issue of a certificate in 1932, no deportation or release,” says the priest.

„The inhuman nature of the communist regime, which built political guilt out of this natural desire to return home, is obvious! It is obviously justified that the Romanian state is now compensating the descendants of political prisoners, at least materially – the years of childhood destroyed, the suffering of parents can no longer be changed.”

Thomas Șindilariu, historian

In the archives of the Teutsch House in Sibiu, Márton’s name is not on the list of deportees from Cisnădie: „He was probably a prisoner of war in camps in Germany, from where he may have tried to come home and was caught,” believes Dr Gerhild Rudolf, cultural referent at the Teutsch House.

Instead, Hermine Márton, Julius Márton’s eldest daughter, appears on the deportation lists. She was sent to forced labour camps in the USSR on 13 January 1945 and repatriated in 1946, „probably because of illness”.

It’s good that they were able to move past all that and move on

In the cemetery of Cisnădie, a warm spring wind is blowing through the pines. At the grave of Julius Márton, there are no signs that anyone has recently passed. The weathered stones are a silent record of the dead of the family left in the Cisnaud soil. Iulius is first, followed by Hermine, Gerhart, Irene…

„I met his wife Hermine, I caught her alive. She was a very nice woman, I went to their house”, says Edmund Márton from Germany, grandson of Iulius.

His grandfather was the brother of Julius. He doesn’t remember ever finding out what Uncle Julius was convicted of or whether he was in the labour camps.

He has lived in Germany for 30 years and was there when Julius son died, and at the funeral of Aunt Hermine. He rarely comes to Cisn[die, and memories fade with the years.

He saw his uncle’s note and found it touching what happened to him and how the message reached us.

The parents kept the secret of their lifes

„We don’t know much of what our grandparents and parents went through. Maybe they didn’t tell us so we wouldn’t be exposed, or resentful. Anyway, it’s good that they were able to get past all that and move on”, Edmund tells me over the phone, in the morning of my visit to Cisnădie.

Three years ago, another message was found at the Constanța Casino, rebuilt in the 1950s with political prisoners.

The note was from a group of 15 prisoners from the Poarta Albă camp, who had been sent to work on the restoration of the Casino.

The letter, which appears to be dated 31 December 1951, was bricked into a window frame, and records the architect and stucco workers, all of whom were prisoners. Juliu Márton also appears, the last, on this list of prisoners who worked at the Casino.

The Saxons from Cisnădie during the years of communist persecution

One of the people from Cisnădie who was taken to forced labour was Gustav Gündisch, a personality of Transylvanian culture.

He was an archivist, historian, document editor. He studied history and geography at the University of Bucharest (1926-1927), being the first history student of Saxon origin), history and theology in Berlin (1928-1929) and history, the auxiliary sciences of history and archival studies at the Institute for Austrian Historical Research (Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung) in Vienna (1929-1932), where he also received his doctorate in philosophy in 1932.

After military service in Alba Iulia and Cluj, he was employed as deputy curator at the Brukenthal Museum in Sibiu, and was then appointed director of the Sibiu City Archive and the Saxon Nation in Sibiu. He was editor of the journal „Deutsche Forschung im Südosten”.

He served in the Romanian army during the Second World War. After the nationalisation of the archive he became cultural advisor to the Higher Consistory of the Evangelical Church C.A. in Romania.

In 1950, he was sentenced to hard labour at the Danube-Black Sea Canal (Poarta Albă-Midia sector, Năvodari) because of his harsh criticism of the communist textbook „History of Romania”, written by Mihail Roller. He stays there for a year. He edits four of the seven volumes of the collection of medieval documents on the history of the Germans in Transylvania.

He published 7 books and 225 studies on the political, cultural, artistic, social-economic and religious history of Transylvania, especially of the Transylvanian Saxons in the Middle Ages and the pre-modern period. He has translated 6 books from Romanian into German, two of them signed by David Prodan.

After the death of his wife he emigrated to Germany in 1982, settling at the Horneck Palace in Gundelsheim where he died in 1996. However, as it was his wish to rest in his native land, he will be brought and buried in Cisnădie.

In 1997, the Cisnădie High School received the name „Gustav Gündisch” in the presence of the Minister of Education.

A small town on the edge of Europe

Cisnădia has an ancient history, most likely dating back to the 12th century. The town was founded by ethnic German settlers called in by the Hungarian royalty to defend the kingdom’s borders against migratory attacks. Historians believe that the town of Ruetel was founded in 1150 on the territory of Cisnădie, which was destroyed a century later by the Mongol invasion.

The first documentary mention of a settlement on the present site dates from 1204.

Heltau was first documented in 1323. As early as 1250 the fortified church of Cisnădie was built in Romanesque style. The church is currently being restored with European funding and is scheduled to be reopened and festively rededicated on 5 August.

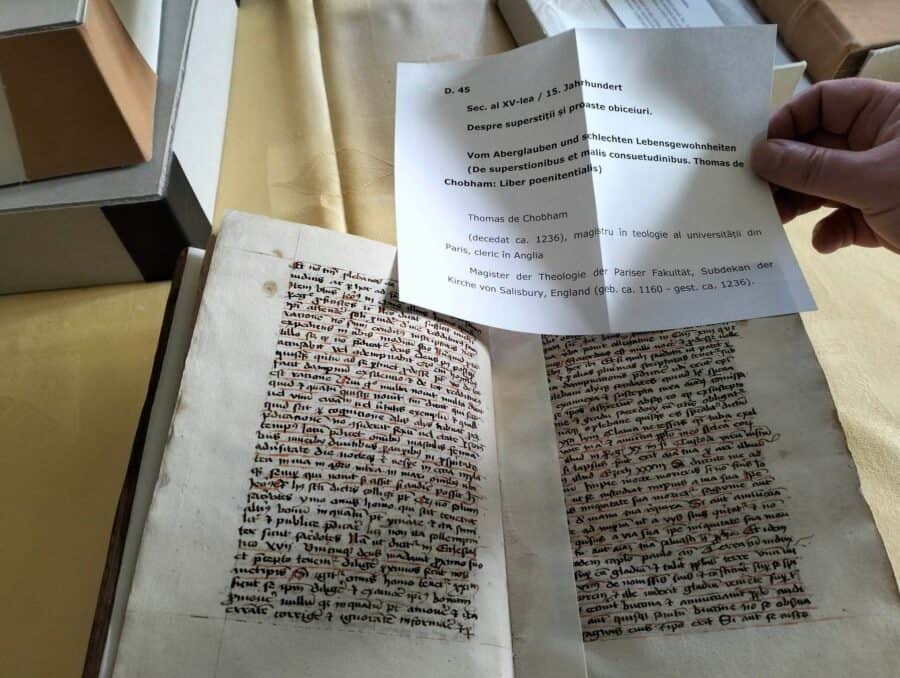

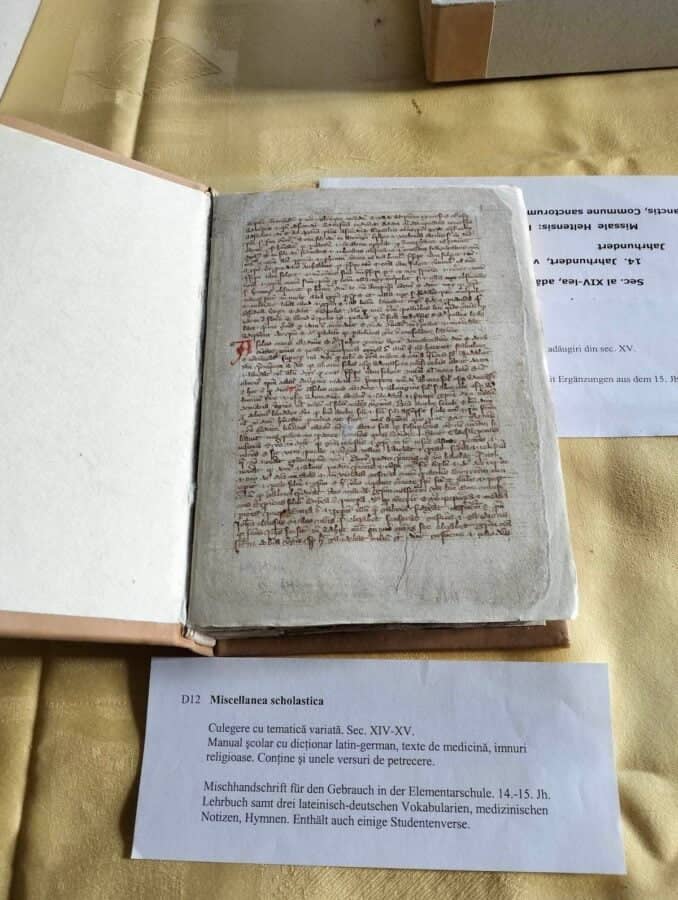

At the Evangelical Church of Cisnădie, a few years ago, a project was carried out to restore a very important book collection, perhaps the oldest and most valuable in that it has been preserved „in situ”, i.e. where it has been used for hundreds of years. The books proved to be a treasure trove for the cultural and theological history of Transylvania.

Twelve manuscripts, four incunabula and seven prints from the 14th-16th centuries have been restored and given back to the church – the oldest village parish library preserved where it has always been used.

The volumes contain religious hymns, advice on superstitions and bad habits, and Latin-German dictionaries.

„It is important to see that although on the borders of Europe, we have always been Europeans. We studied in Europe and were interested in the ideas circulating in the West, we went to buy, to get books, even if they may have cost a fortune back then,” says the parish priest of the Evangelical Church of Cisnădie.

Cisnădie’s last great test

In the Second World War, some 500 Cisnădie residents were called up. Of these 143 fell on the battlefield. In 1944 the Soviet army set up a camp for prisoners in Cisnădie.

In 1945, 870 men and women of German origin from Cisnădie were deported to forced labour in the Soviet Union, of whom 35 died. Most of those who survived returned to Cisnădie in 1949, the others were taken to Germany.

The 1941 census revealed that Cisnădie had 5,385 inhabitants, of whom 3,691 were ethnic Germans.

In the 1950s the exodus of Transylvanian Saxons to the Federal Republic of Germany began, mainly for the sake of family reunification, where men had been deported after the Second World War.

After 1989 the pace of emigration increased greatly, completing the exodus of the local Saxons. There are now 284 Evangelicals.

Follow PressHUB on Google News !

Photo: Julius Márton, writing the note he left on the wall of the Constanta Casino. Illustration made with DALL-E, AI software